One simple philosophy has guided Melbourne’s Newsboys since 1893. Build the boy or girl right and you make the world right, writes Gary Tippet.

“THOSE eyes and that smile,” the well-dressed woman told the 12-year-old boy. “They’ll get you into trouble one day.”

“Aw, fair go missus,” thought Bob Urquhart. After all, those qualities were among his greatest assets as a Melbourne newsboy. Without them, all he’d have would be his quick patter and his street-smarts and what today we’d call his work-ethic.

It was 1946 and Bob was outside King’s Hotel at the corner of Russell and Little Collins Streets. He was a little bloke with swept-back dark hair, but an untameable forelock that kept falling over one of his sparkling eyes.

He wore a threadbare V-neck jumper over a shapeless open-necked shirt. Across his left shoulder was the leather strap of his money bag and over the other, a wider loop of belt into which he jammed a small stack of his evening papers: The Herald – or, as he would yell, over and over, “‘ERRR-ALLD!!”

The spot outside King’s was Bob’s stand, the position allocated to him by Carroll’s, the nearby newsagents. It was his first stand and not a bad one, though Flinders Street – on the station steps or outside Young & Jackson’s pub – that was the plum.

Still, this was pretty handy with passing office and shop workers knocking off and lots of drinkers – and drinkers meant tips or zacs mistakenly handed over instead of threepenny bits. There were the ladies in the pub kitchen who’d slip him a couple of baked spuds every so often. And he’d created a little round he’d work before settling into his stand: in the back door of George’s to deliver Final Extras to shoppers and staff then down to the back of the Tivoli where he’d become a favourite of the performers and chorus girls.

Those eyes and that smile.

He’d been utilising those assets since he was 10, when he started selling papers – and getting his street education – in Melville Road, near his Housing Commission home in West Brunswick. “Standing on the corner, hopping on and off trams to sell a few extras,” recalls Bob, now 79. “It’s a wonder I never got killed.”

He shifted to a spot outside an Essendon hotel. The pub had its own SP bookie and every so often the coppers would descend: “Suddenly there’d be people going everywhere, bookies and punters jumping the fence and bolting down the laneway.”

The job was never for pocket money, most of what Bob earned went into the family kitty. His father, a sometime labourer and horse and cart driver, had “just disappeared eventually”.

“Mum struggled along on her own, just went out and worked day and night to keep us all together. Sometimes we really didn’t know where the next meal was coming from, but something always turned up. She made it to 101, God bless her.”

As soon as he turned 12 and was eligible for a city newsboys’ licence, Bob followed his brother Joe into the city and took his stand outside King’s – for a while: “Whenever a better corner came up you’d try and grab it.” He took a spot at the Leviathan Stores on the corner of Bourke and Swanston and later, a plum, outside the Town Hall.

“It was twopence for a paper and we used to get sixpence for a dozen. Outside the Town Hall some nights we’d sell 60 dozen in a night, so it was good money. We used to get tips too, especially at Christmas. I’d get about £5 a week, real good money at a time when the ordinary worker was getting £10.’’

Bob worked from 4.30 to 6.30, six nights a week. “You’d race in after school, pick up your first lot of papers, the Herald, at the shop and all the other editions would be dropped off at the stand you were on. There was the first, which was the City. There was a City Extra, a Home and the Final. On Saturday nights there was the Sporting Globe.

“You had to have a shout if you wanted to sell and I’d practised mine. I remember standing the tram one night going home, dog-tired, and suddenly yelling it out: ‘Getcha ‘Erald!’. It just came out, and everyone laughed and I thought ‘you idiot’.”

It was a good life though it could get “a bit hairy” out on the streets. “We were dealing with drunks, there’d be fights and sometimes, what these days we’d call paedophiles. We just had to learn to fend for ourselves: you grew up tougher and more self-reliant.

“But I was a pretty easy-going person all me life, people tell me,” he says. “I smiled all the time, I never got upset and I enjoyed life. That worked in my favour selling papers.”

Bob kept his stands until he was 16 when he took an apprenticeship at Specialty Press printers in Little Collins Street, where he used to deliver papers and, three years in a row, tip the boss the winner of the Melbourne Cup.

Sixty something years later, he still misses it. “There was a newsboy on most corners. They were part of the fabric of Melbourne. They were part of the life and the sights and the sounds of this city.

“ ‘Cos we were cheeky little buggers, us newsboys. Cheeky and loud. But people like that in Australia.”

And those eyes and that smile.

A BOUQUET FOR THE NEWSBOY

“THE NEWSBOY is in business in a big way. He deals in immensities. A superficial observer may say he is selling paper. He is doing nothing of the kind…

“…The paper sold by the newsboy counts for nothing; it is the news, and the news alone, that matters. He who thinks of a newsboy as merely a vendor of paper fails to recognise both the dignity of the boy’s office and his vital niche in the scheme of things.

“A newsboy deals not in paper, but in earthquakes, wars and revolutions, in fires, famines and pestilences, in assassinations, abdications and coronations, with a few test matches and similar trifles thrown in for good measure. Other tradesmen deal in coats, coals and cabbages; but the newsboy sells you cathedrals and palaces, he offers you the Houses of Parliament and the stock exchange; he holds in his hand all earth’s most imposing structures and all the ships that sail the seven seas.

“The point is that the whole world is wrapped up in every paper that the newsboy sells. The city urchin who weaves his way among the traffic to effect a sale, and the country lad who sets out from a store to carry the paper to the homestead over the hill, are both like Atlas – they bear the entire globe with them…

“The wares in which the newsboy deals are the very commodities that every man most passionately craves.”

The Age, 1956

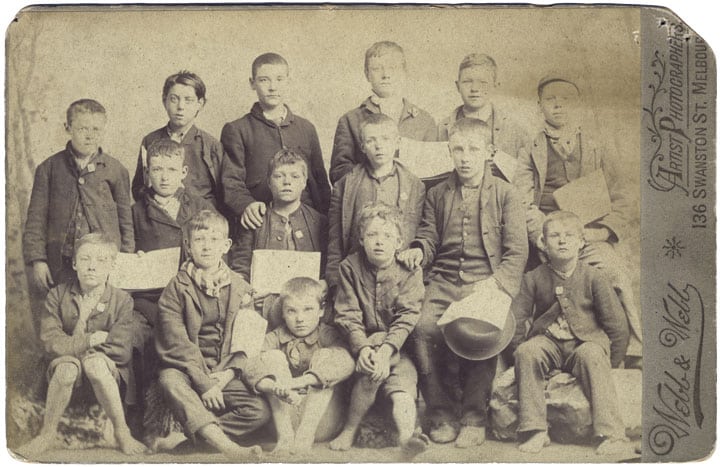

THE BOYS OF ‘97

THERE is a studio photograph, faded and creased, of 15 boys aged, probably, from seven into the early teens. They’re staring intently, almost distrustfully into the camera. Not one of them smiles.

A few are in knee-high pants, the rest in over-sized long ’uns. All wear drooping, formless jackets, some are in vests and a couple have scarves tightly wrapped around their throats. One boy’s sleeve hangs at the shoulder by a couple of threads. All but a few are barefoot. Half a dozen are holding broadsheet newspapers.

On the back of the photograph, originally written in pencil but now inked over by a fountain pen, is a note from Miss Edith Onians: “My first boys in 1897”.

One wet afternoon late the previous year she had come across the first of those skinny children – Melbourne newsboys – as they waited for a delivery of papers. They were floating bits of of wood with improvised sails down the flowing gutters, wagering their pitifully small earnings on the race. Most were intermittently homeless, dossing down, when the money ran out, on the riverbank or in the Richmond paddock over by the old morgue, “with the ‘dossers’ dog’ for pal”. None could read or write.

It was what has been called “the hungry, gas-lit era of the bank crashes” and 28-year-old Edith Charlotte Onians, the daughter of devout and wealthy Anglicans who were influential in the 19th Century Sunday School Movement, was beginning a lifetime’s devotion to the underprivileged boys of Melbourne. She had recently started volunteering at William Mark Forster’s City Newsboys’ Try Society – which would eventually become known as the Melbourne Newsboys’ Club – founded in 1893. She asked the boys if they would come to a school class if she started one there. They said they’d give it a go.

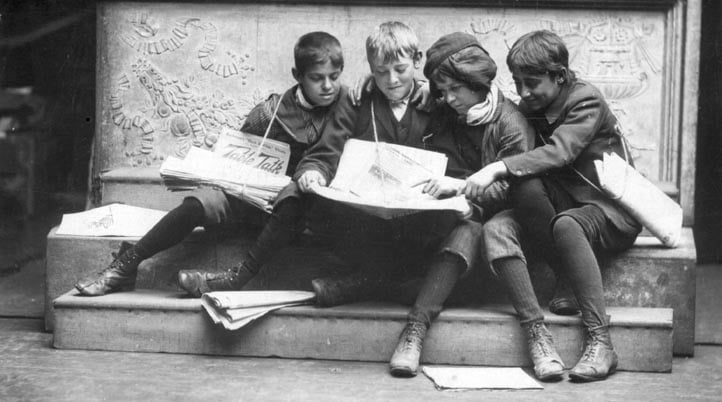

As Michelle Smith noted in her thesis: Edith Onians, A Biography, by the 1890s Melbourne had a population of half a million and they all loved their papers. In 1883, writer R.E. N. Twopenny had described Australia as “essentially a land of newspapers” and nowhere was that more true than Melbourne. In that decade the circulation of The Age rose from 40,000 to 100,000 despite competition from a host of other publications and the city’s streets “teemed with newspaper boys”.

Most, like the first fifteen, came from terribly poor families, if they weren’t homeless and alone. In streets that were a din of noise and raucous cries of street vendors, “one of the main culprits was the newspaper seller,” wrote Smith. Many citizens considered them as a loud and obnoxious annoyance.”

Edith Onians thought otherwise: “Those who did not know them called the newsboys ‘roughs’ and, in the Australian vernacular, ‘larrikins’,” she wrote half a century later. “I knew the boys better… I never once heard a curse or a word of filth, and bigger or more loyal hearts I have never known.”

At the time of her writing, she had been “on terms of personal friendship with no fewer than 15,000 boys” but those first boys – among them “Battler’’, “Fiddler”, “Soldier” and “Tabby Cats” – were “second to none in their perseverance, their loyalty and their big-heartedness”. And for many, then and long after, “their only shelter, and the only place where they found friendship, was our club room”.

That year of 1897, the Try Society’s second annual report attempted to “furnish a few explanatory particulars” of its aims and operations.

“In ours, as in all city communities, there is a large section of society who enjoy little or no home life… These adverse conditions are productive in a given ratio of so much ill health, drunkenness and general depravity, (and are) prolific of the most degrading consequences to the rising generation…

“…The parents of many of our members are of the poorest class, who, in order to eke out a bare living, are forced to send their children into the streets to sell papers, matches, flowers, &c…

“At our Hall, 192 Little Collins Street, boys of the humblest social grade ever find a heart and a hand ready to help them when sympathy and practical assistance is needed. There we furnish a resort for them where innocent and recreative amusements and instruction are supplied… such as will induce them to abandon our back slums and lanes, where the cultivation of evil practices is the rule, not the exception.”

But perhaps the Street Boys’ Song in the Try Excelsior News back in 1893 put it even better:

Down in the haunts of the city,

Mid the darkness of squalor and sin,

We find the poor lads we are seeking,

And tenderly gather them in.

Miss Onians’ first classes, in the basement of the Cyclorama Building, were in literacy and elementary Three Rs (though on Sundays she taught her often reluctant and sceptical boys at Sunday School). But, increasingly, there was much more on offer: daily hot meals for a penny, second-hand clothing, trade skills and what the old report called “innocent games and other amusements”.

By 1907, four years after the club had moved to new premises at 20 Coromandel Place, off Little Collins, membership numbers had climbed to 700 and there were waiting lists for trade classes such as carpentry and, particularly, boot repair.

Boot repair had become part of the club’s ethos – perhaps due to the barefoot poverty of its first members – and it was expected that all boys should know the basics. Soon the Children’s Welfare Conference program would read: “Now one rarely sees the city newsboy down at heel, with his toes sticking out of ragged boots, simply because he is taught to mend his shoes.”

It taught them so much more: not least of which was that they were valued.

Miss Onians – always Miss to her thousands of newsboys – wrote a little book called Read All About It in 1953. It was a loving, perhaps even rose-coloured, testament to those boys, but in its foreword she explained her, and the Newsboys’ Club’s, credo:

“I believe sincerely that no boy… is irreclaimable. Every youngster with a mind born into Australia is a potential source of wealth and happiness (and) is capable of being turned, by appropriate treatment, into a useful citizen.” She had no doubt about that: “Doubt paralyses; only certainty achieves.”

When she died two years later, Percy Rogers, one of her earliest old boys (and Soldier’s little brother, unsurprisingly nicknamed Little Soldier) then living in Boston, wrote to the club: “Her passing took me back about 54 years when I first met her. I was a poor ragged hungry kid. I had never been to school and could not spell cat. She taught me to read.

“She fed me and clothed me and taught me the difference between right and wrong.”

THREE FLOORS OF THINGS TO DO

WAYNE Bunte turned up at the Melbourne Newsboys Club one evening in 1955. He was nine years old and had been selling papers in Hawksburn and Toorak for the last couple of years to help his young widowed mother. She had sent him into the club that night because she thought it would be good for the quiet little boy.

But Wayne could barely get his head above the counter and the lady there told him to come back when he was older and bigger. As soon as he turned 11 he was back and discovered Wednesday evening basketball.

“I used to look forward to it every week,” he recalls. “I couldn’t wait for Wednesday to come around. It was green, that was our team colour, and that was my night. Even now when I buy a Tatts ticket, I’ll always buy it on a Wednesday.”

Angelo Diiorio joined in 1962. He’d been selling newspapers around Fitzroy and Carlton since he was six, taking home up to £1 a week to top up the £8 his father earned with the Victorian Railways. But compared with what he might earn on a city corner he knew that was “peanuts”. He took himself into town when he was 10, but couldn’t get a city newsboy’s licence until he turned 12.

But he did find the Newsboy’s Club.

“I saw opportunity,” he remembers. “This was a club that wanted no money, no joining fees, but they were prepared to share all their knowledge and experiences with me. Ross Smith, who won the Brownlow Medal, the captain of St Kilda, he was my first coach at basketball. A beautiful man.

“When I started there was free dental, medical, you could get a haircut. There was an English teacher, a swimming teacher, arts and crafts, boxing, wrestling and basketball. Imagine that.”

When 12-year-old Bob Urquhart joined the club soon after getting his first stand in 1946, it was at its third and final location at 109-117 Little Collins Street, on the site of the old Adam and Eve Hotel, famed haunt of the poet Adam Lindsay Gordon. Bob was overwhelmed:

“It was three floors of things to do.”

Back in 1897, its predecessor, the Society, had offered “a new branch of work”, the first boot repairing class, though carpentry had not been held lately, owing to the want of a practical instructor: “These useful handicraft classes are part of a newsboy’s technical education, to aid him somewhat in becoming at a later age a more useful citizen than he would otherwise be without them.”

There were Educational Classes on Wednesday, Thursday and Monday mornings “under the charge of our ever-willing honorary teachers, Misses Lorimer, Mead and Onians”. Their self-denying labours and personal contact, said the report, had seen a marked improvement in the general conduct of their charges.

There were also gymnastic and dumb-bell classes under the guidance of a Mr Nelson. There was the Boys’ Penny Savings Bank with its 72 depositors and 883 transactions since the previous September and its aim of inculcating in the boys “thrifty and provident habits”.

Until then, it noted, “the boys’ spare cash was often employed in juvenile gambling (pitch-and-toss, boat-racing etc.), which has much diminished among them”.

Finally, “another great attraction we offer to these poor lads is our Coffee Room where plain wholesome food can be obtained at nominal price. Our object in making a small charge is to avoid pauperising the boys, and as a rule they are able and willing to pay for what is supplied to them.” If, however, the club was satisfied a boy could not pay, he was never permitted to go without a meal. That year £46 11s had been paid by boys for an estimated 9000 meals.

Here were the foundations of the Newsboys’ Club’s services – which, like the premises – continued to grow and diversify. There is a yellowing page of indeterminate date, a List Of Our Classes And Evenings On Which They Are Held. It is a single page of very small type and very large attractions for struggling newsboys.

The club was open from 10am to 9pm except Saturdays. All classes started at 7.30 pm.

On Monday they began with the enrolment of new members. Then there were medical examinations, under Dr Frederick White, as well as free dental treatment. There was cabinet making; turning and fitting; and boot repairing. There was library; quiet games and hairdressing provided by old boys A. Dunstan and S. Fowler. (Sam Fowler was resident barber for 20 years and held the voluntary position until his death. Miss Onians later reported that he had trimmed 7200 boys’ hair). Then there were sports: basketball, wrestling, swimming and lifesaving and games.

And then there was Tuesday:

Cabinet making, wood turning and French polishing; electrical engineering, metal work and wireless; the scout troop, 13th Melb. (Edith Onians’ Own); sign and ticket writing; and basketball.

On Wednesday:

Turning and fitting; body-building with weights; boxing; physical training, gymnastics and basketball; and swimming and games.

On Thursday:

Cabinet making; boot repairing; library; hairdressing; first aid with ambulance officer Frank Saunders; basketball (they loved their basketball at the Newsboy’s Club); wrestling; swimming; and games.

On Friday nights there were no classes. Perhaps they thought that otherwise the boys would never see their families.

On Saturday there was cricket, football or athletics and on Sunday Miss Onians still conducted Sunday School.

But that wasn’t all: On alternate Wednesdays there was a welcome for the wives of old boys and a baby clinic; an adult education centre for old boys, held monthly; cinema entertainments; and, two afternoons each month, an honorary opticians’ clinic. There were mid-day meals each afternoon from noon until 2pm and Hot Night Dinners from 5.30 until 7pm.

The page listed 45 honorary workers and Miss Onians, by then honorary secretary, and assistant secretary A.N. (Norman) Craig were also available as probation officers (which might give the lie to her view that all newsboys were perfect little souls).

By 1956 new classes had been added: Motor mechanics; model building; light handcrafts; physical development; visual education; and table tennis.

“It was just a wonder,” recalls Bob Urquhart. “A revelation. They never had anything like that out where I lived. This was a totally new thing, well ahead of its time.

“There were hot meals at a penny a course. For threepence you got a soup then a main course of meat and vegies and a sweet. I used to eat there three nights a week and that took a bit of pressure off mum.’’

By then there was a 110-acre holiday camp, Millgrove, on the Yarra near Warburton. “We went up there when they first got it and had to clear out all the swampland,” remembers Bob. “I loved it. First of all we were living in tents. We’d fish in the creek and do long treks of walking – it was fantastic doing that in the night when it was pitch black. We used to go up there on the old Puffing Billy. It was all new experiences for a kid from the inner suburbs.”

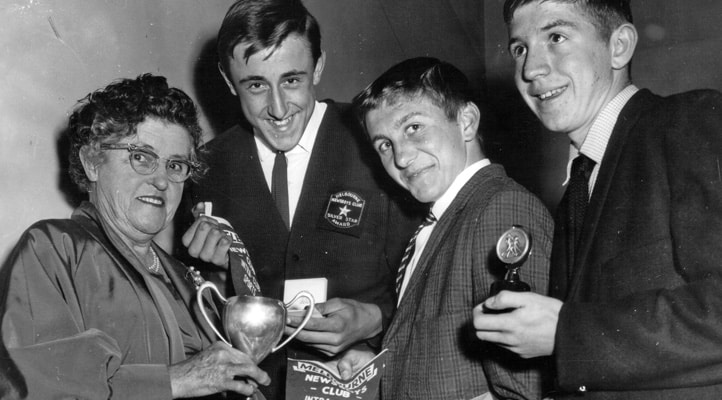

Bob had blossomed within those three floors of things to do. In 1947 he was chosen as Melbourne Newsboy of the Year and won a trip to Tasmania: “I had a reporter go over with me and I even got a write-up in the Hobart paper, the Mercury. For a kid from Brunswick, that was ‘overseas’.”

He had taken up wrestling and in 1947 won the club’s silver cup for most improved wrestler. A couple of years later he represented Australia in a competition against New Zealand, wrestling a draw with the runner-up of the Empire Games. By 1956 he was one of the club’s coaches.

“The Newsboys Club changed my life,” he says. “It led me to the work I eventually did; I learned a lot about leadership; and you met a lot of people you’d otherwise never rub shoulders with – I met the Governor-General, royalty, big business people like Sir Keith and Dame Elizabeth Murdoch.

“I joined the club at 12 and I was a leader there until I was 23 or 24. It was a really big, influential part of my life and made me the man I became.”

THE MEN THEY BECAME

WHEN William Mark Forster began the precursor to the Melbourne City Newsboys’ Society in the early 1880s, he called it the Try Society. In that name was Forster’s original ethos: to instil in children the message that if they would only “try”, that is make an effort at their studies, sports, work or interests they could become good citizens and achieve success.

That second annual Newsboy’s report in 1897 put it like this: It was the boys of the poorest and most wretched section of society “amongst whom we work and whose moral and social condition we are trying to ameliorate… Many of them have very hard lives, and give abundance of evidence of possessing many of those qualities which are essential in the development of desirable citizens, if only helped in time, and in the right way.”

For many years there was a slogan, sign-written around the walls of the Newsboys’ Club’s main hall: “Not to make money but to make men is the noblest purpose in life.”

And for Edith Onians that was the aim: to build, as she later titled a book, The Men of To-Morrow. Ever the Sunday School teacher, she liked to quote a favourite poem:

Who touches a boy by the Master’s plan.

Is shaping the house of the future man

But she put it more eloquently in a funny little parable she liked to tell. It concerned a father who, to amuse his small son – or more likely himself – cut up a map of the world and said to the boy, “Now put the world together again”.

The boy did it very quickly and the father asked how he had managed it. “Well dad,” he answered. “There was a picture of a boy on the other side. I just built the boy right and that made the world right”.

The Newsboys’ Club aimed to build boys right and Miss Onians seemed to truly believe it had done that with every one.

She wrote proudly of the 626 one-time members who went off to the First World War “to fight for a land of which they owned not an inch”. Boys like Alf Gardiner, killed at Lone Pine; Mick who died at the battle of Bapaume; and Sport, killed on Christmas Day 1916 on the Somme. And those who died in the next war, in North Africa and the skies over Germany.

It is said Miss Onians visited the home of every boy who joined the club and knew every one of their names: “These boys, mates by instinct, have shown they had in them the makings of men who could, and did, serve humanity in the finest fields of citizenship, in peace and war.”

In January 1960, someone at the Newsboys Club sent a note to Fred Flowers, sales Manager at the Herald and Weekly Times. It is unclear what request it was responding to, but it began:

“Dear Fred, Enclosed are the names of several folk who have acquitted themselves well in several spheres. But I do not feel they are what you require. I just cannot think of any one in prominence at this moment…”

And then the writer provided a list over two pages proving him or herself very much mistaken:

Under Professional Occupations there was Ecclesiastical: Rev. M.R.T. Hazel, Church of England; Law: Roy Hanger, Barrister; Dentistry, Frank Barnett; Mechanical and Electrical Engineering: Brian Saunders and Alfred Gardiner. There was a State Cabinet Minister, the Hon. William Barry, and Charles Mutton, MLA, and John H. Morris, twice Mayor of Coburg.

There were boxers such as Norm Gent, a Victorian title-holder, and Bill Seewitz, former amateur welterweight champion; Victorian champion wrestlers, Bill Davies, Paul Buckley and Olympian Bob Clarke; footballers, Fitzroy captain Alan (Butch) Gale and North Melbourne skipper Les Foote, both of whom had played for Victoria; jockeys, Vic Hartney who won the 1943 Melbourne Cup on Dark Felt, and leading apprentice Bobby Ball; a weightlifter, Australian middleweight champion, Len Woodhouse; a walker, Harry Somers; and basketballers, All-Australian Tommy Nash and state representatives Eric Lund and Norm Davenport.

And then there was William Pettigrove, horticulturalist and champion rose grower who had just won best bloom in the National Rose Society’s annual Spring show.

Miss Onians might have added a librarian, another mayor or two, a president of the Returned Sailor’s, Soldier’s and Airmen’s Imperial League of Australia, a special magistrate of the Children’s Court, a bunch of tram conductors, a bookie (“at the top of his calling as his training befits him”) and Little Soldier over in Boston, “a successful chef in a big way of business”. And she’d certainly have included thousands of other newsboys who grew up to be good fathers, loving husbands, hard workers, caring businessmen and compassionate citizens.

And then there were former club leaders like Wayne Bunte who took his love of basketball to the Balwyn YMCA and set up a club there and later ran a community centre at Doncaster. Or Bob Urquhart who swapped a career in printing for community services, working in the youth justice system with troubled boys in detention.

Or Angelo Diiorio who went on to run a basketball league for boys and girls in the northern suburbs, owned restaurants in Melbourne and Queensland and now, at 63, is a direct care worker in disability care. “I learned most of my skills for this job through the club,” says Angelo.

“They taught me that giving in life is so much more important than receiving in life.”

FORMING A FOUNDATION

In mid 1973 the Melbourne Newsboys’ Club published its 80th annual report. On its cover was another photograph, but not of ragged, wary, unsmiling and barefoot boys. These were five grinning, bright-eyed kids in shorts, t-shirts and sandshoes, happily grappling with a burly wrestler in the club gym.

But they wouldn’t be wrestling there any more. There had been momentous changes at the club and that year, the report told its readers, had been perhaps the most “momentous one in our history.”

Inside it reported, in dry, soothing language, that increasingly there had been a number of problems “encountered, not only by our club, but by almost all charitable organisations involved with the welfare of young people.”

For the Newsboys’ Club specifically, these included “insufficient finance to provide for annual maintenance, resulting in annual deficits amounting to $6000 in some years”, and questions about whether the club could continue at Little Collins Street “in light of a valuation of approximately $700,000 for its city site”.

Enrolments and attendances had been declining since the 1950s. In 1952 only 88 boys had joined and now, as the suburbs spread out from the centre, there was more competition from local clubs such as YMCAs and scout troops.

The legal age for selling papers in the city had been raised from 12 to 15 and so there were fewer newsboys. Many stands had been taken over by pensioners. Increasingly, parents were reluctant to let their boys travel long distances to and from the city at night. There was a fear of growing violence especially on trains.

The club had also fallen into some disrepair. Wayne Bunte, then a leader, recalls Nauru House being built on the adjoining corner of Collins and Exhibition. As its sub-floors and foundations were dug, the dynamiting and drilling had cracked the club’s swimming pool, rendering it unusable for years.

And so it was decided that the premises, along with Millgrove camp, would be sold, the proceeds invested to provide income sufficient to make grants to the increasing numbers of youth organisations: “(The) aim, as always, being to help young people in Metropolitan Melbourne.”

That, it said, might include helping established clubs with maintenance costs, probably in the area of professional and qualified leadership, and encouraging special services, such as after-school groups.

It could be promoting “attractive social-recreation areas” in clubs “for older children or young people who tend to frequent milk bars and unsavoury coffee shops”. It might entail encouraging “new and experimental youth programs – both short- and long-term”.

The club was evolving for a new world, but not without pain. “I was broken-hearted when it closed,” recalls Angelo Diiorio.

The premises sold for $775,000 and, along with donations from community members, the proceeds were carefully invested. With $806,456 in 1974, the club – now acting as a foundation, though the name Newsboys’ Foundation would not be finally approved until 2007 – allocated grants totalling $16,177.

The following year allocations grew to $38,076 in sums from $50 (to the Richmond Boys Club for trophies and awards) to $4000 (to the Child Welfare Foundation of Victoria for the development of services to disadvantaged youth).

There were grants to the Australian Birthright Movement towards the maintenance of one-parent children; the Children’s Protection Society for the maintenance of an emergency unit for children at risk; youth clubs and centres in Caulfield, Clayton, Oak Park, Richmond and Lalor and Thomastown; and the Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind and the Royal Victorian School for the Deaf for playground equipment. They helped pay for buses at the Try Youth Clubs and the Broadmeadows Youth Services; a training film for the Spina Bifida Association; and, never forgetting the past, equipment and hall hire for the Newsboys’ Club Leaders Basketball Contest.

The following year grants topped $50,000 and, until the introduction of the GST had its dampening effect, they were approaching $1 million a year. Allocations fell to around $600,000 but since have climbed, despite impacts such as the Global Financial Crisis, to $735,530 in 2011 and $710,015 in 2012.

Last year funds went to 40 groups and services, from the Ardoch Youth Foundation to the YSAS South Pacific Islands Rugby Project. They went for indigenous education scholarships, a camping program for intellectually disabled students, to put a financially disadvantaged student into the Australian ballet school, and to a nutritious food program and a deep maths program.

Since 1974 the Foundation has allocated more than $12.2 million to fulfil its simple historical vision: “That all Victorian disadvantaged young people have the opportunity to reach their full potential”.

Specifically, says Chief Executive Sandy Shaw, it’s young people aged 11 to 18, from disadvantaged backgrounds: “Now that’s a fairly broad brush: low SES, indigenous, rural and regional youth, asylum seekers and refugees. We try not to get too siloed about who these kids are and what they might look like. It’s a much more holistic look at life and the experience of disadvantage.

It’s the kids who have dropped out of life or are at risk of dropping out, she says.

“It’s about trying to re-engage kids in a positive way into their community, into learning and particularly education. Whether it’s a schools based program or community based, whether it be art or sport, outdoor education, it’s about reconnecting kids and we’re very open about what it might take to get there.

“I think it’s really consistent with the original aims. It’s about providing kids with an opportunity to grab and to improve their lot in life. That was the reason for being 120 years ago and it’s still our reason for being now.”

Bob Urquhart says that at the Newsboys’ Club kids learned that they were of value, that there was a better future for them: “They’re a foundation now, but they’re still doing the same job, looking after kids who are doing it tough, helping them get over the barriers that disadvantage puts in front of them.”

Wayne Bunte has returned to the Newsboys’ as a board member and says the “theme” of the club has never changed. “It helps those who are in need and it helps them to achieve their best. So the principle for Newsboys hasn’t altered at all – it’s just not all confined to one building anymore.”

Bob Urquhart

NEWSBOYS… FOREVER

“WHAT I learned from the club, that I passed on as a coach to probably 300 or 400 basketballers that I met on the way, was that it was nothing about their ability. It was their participation.

“I had 15 kids, three nights a week, coming in with no idea about basketball or what teamwork is. Six months down the track these kids are seeing another part of their life has opened up. To see them progress, you have no idea of the joy that gave me.

“Newsboys’ was just so important to me. I had someone that cared about me, someone that was interested in me, and people that would spend time with me, where my mum and dad, working all the time, couldn’t give me that. So I made them my family.”

Angelo Diiorio, 63, newsboy

“THE principles were good. They had a principle of attendance because they felt that if you really wanted to get on in life you had to be reliable and dependable.

“It was structure. You could go in and enjoy yourself, but you couldn’t just run around. You had to be involved in an activity. They encouraged you to be reliable through the certificates and attendance, you learned something from doing an activity and you also enjoyed it because you were mixing with people like yourself.

“I never left. The connection was always there. I used to go to all the Newsboys’ meetings. I’ve never ever gone away from it.

“I was invited on to the Board in 2005 and I’ve been there ever since. The main thing I get out of it, I think, are the applications we get every month, wanting money to help younger people in need.

“There could be a child from a family that’s very poor but that child has a gift and they just need encouragement to really bloom. It could be in education, it could be in the arts. And we can really help. Then it’s up to them to take it from there.”

Wayne Bunte, 67, newsboy

“THE Newsboys Club changed my life…

“I wrestled and later became the wrestling instructor. I played table tennis and billiards. I was in the woodwork and boot repairing classes. I played basketball, we had a football team and I was in the scout troop: ‘Edith Onians’ Own’. I spent a lot of time there right up until I was a young man. When I first got married I was never home and eventually my wife said something like, it was the club or her.

“But I still kept contact. I still go to the AGMs. When you work it out, I’ve been in the Newsboys Club now for 67 years. It’s still a part of me.

“I think the club’s pretty much forgotten by most people now. It’s a part of Melbourne that’s been lost, but it was something wonderful for the thousands of kids who passed through its doors, particularly those who had no money. It helped them when they were struggling and it was a place where they could have fun, where they could learn valuable skills and to stand on their own two feet.

“It set a lot of us up for a better life than we might have had without it. They were very impressive people in there.”

Bob Urquhart, 79, newsboy

(Who, by the way, still has those eyes and that smile.)